The comadre-hood is a sisterhood of strong women with shared humor, interests, and background. Technically speaking, a ‘comadre’ is someone you choose to be a godmother to your children (and is then, in turn, a madrina or nina to your children). In the Mexican culture, it is usually made official in the church during a baptism ceremony; it sort of seals the deal. But I believe that the church doesn’t necessarily legitimize comadre-hood, but rather, it is legitimized by mutual love, respect, and true solidarity; it is a sacred female alliance bonded by the little things (and the big things) that connect us as mothers and as women. What makes it special is the vulnerability in which intimacy grows.

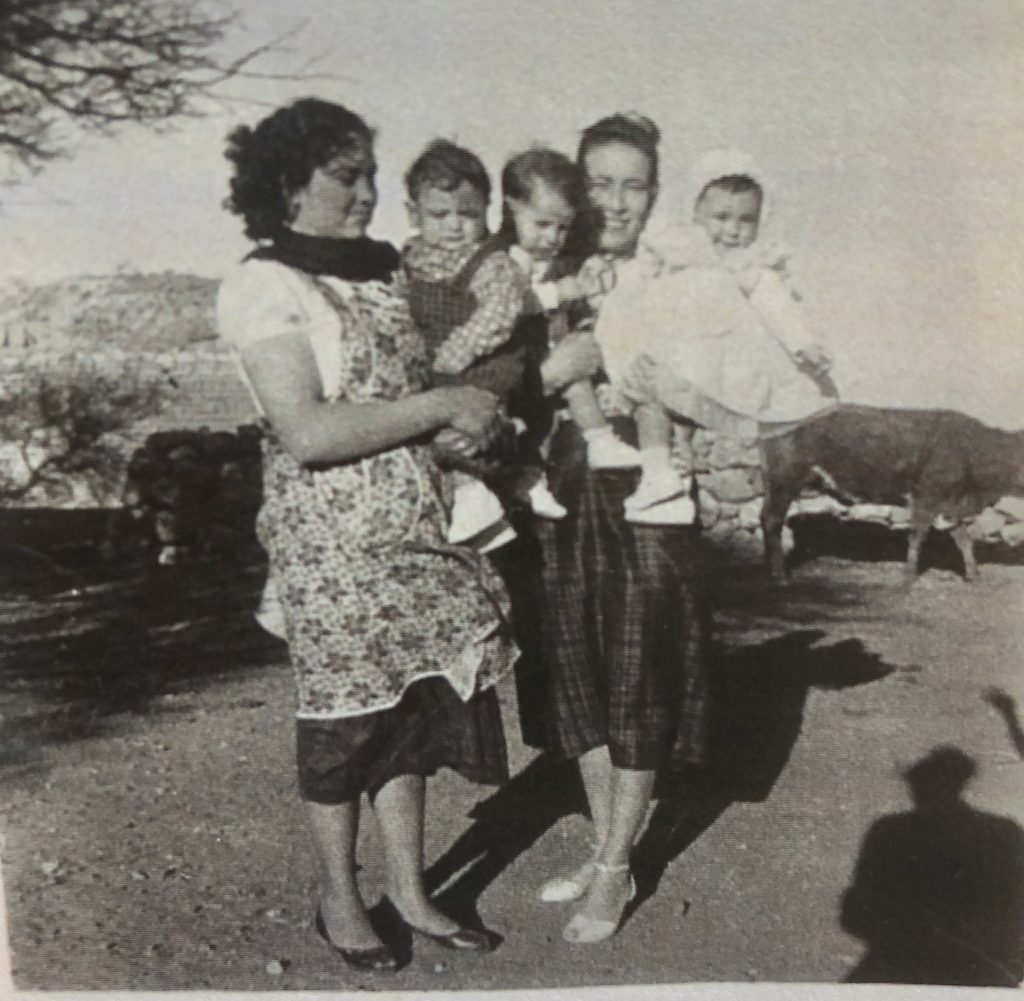

As a young child, I first witnessed it in my grandmother’s modest kitchen when she and her comadres would sit around the table in their aprons, elbow deep in masa, making tamales together. They would laugh, speaking in Spanish and playfully critiquing each other’s techniques. This was just as sacred as any baptism in a church.

My grandmother was incredibly charismatic, a hardworking, resourceful, and humble woman who emigrated to the United States in the 1950s with her husband. Later, she divorced and spent the latter part of her adult life alone…but she was never truly alone because her house was always a meeting place for women. All of her official and unofficial comadres would often come over unannounced to have a cafecito con pan in the middle of the afternoon, watch a novela with her, or go to the senior center for an evening dance event.

She even went on vacations with her comadres to places like Puerto Vallarta, she loved a lovely beach and warm ocean to float in. As my grandmother got older and was more confined to her home, the comadrehood gradually changed. The tamale making waned, but her friends never stopped visiting, often bringing her flowers, food, or produce from the local stand. They would take her to church on Sundays, once driving herself proved risky at 85.

In my own mother’s circles, the sisterhood was a bit more progressive…. many of the women had higher education degrees, some of them the first in their families to obtain this, and most of them teachers in the community trying to make a difference in the lives of their students. I remember the pages of Gabriel Garcia Marquez and portraits of Frida Kahlo and Cesar Chavez displayed proudly in their homes. For educators and activists who upheld postmodern feminist standards but paid equal homage to the old traditions of their mothers, cooking remained that vehicle.

I have vivid memories of my mother’s comadre Graciela and being in her kitchen as a young girl, watching the women make quail in rose petal sauce, a dish from the book ‘Like Water for Chocolate’ that they had read together. I can recall the joy, laughter, and pride in their voices as they discussed Chicano literature, all while making the tortillas and roasting the chiles.

In my own life, my official and unofficial comadres are all women who would protect and care for my children as if they were their own, the women I don’t have to clean up for before they come over for a cafecito con pan. There are the comadres with which I share a rich history, but there are also the newer friendships where we ‘get’ each other and never feel the need to put on airs. These days, we are more likely to go out for a delicious meal at a cool restaurant in town. We commiserate over our collective exhaustion as moms trying to do it all; we talk about our kids and their struggles, offering grace and sharing a remedy or two. We might also talk about our generational trauma and how we break cycles, congratulating each other on breakthroughs. But when this busy life keeps us apart, my favorite way to connect is by sharing funny memes, knowing that it will make the other laugh out loud while we are elbows deep in laundry, home with a sick kid, or in tears over the global state of affairs.

The comadre-hood keeps me going; it ultimately keeps hope alive in this weary world.